Published on

How these Northeastern researchers are rewriting the immigration-crime narrative

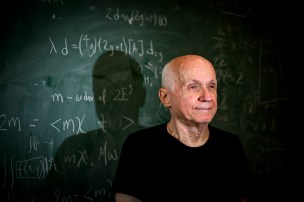

Northeastern’s Ramiro Martinez and Jacob Stowell say their research over the past three decades has disproved mistaken assertions that immigration exposes American communities to increases in crime.

When Ramiro Martinez began his study of Latino crime in the United States 30 years ago, he thought he knew what to expect.

“I assumed that places that had more immigrants would have more homicides,” says Martinez, a Northeastern University professor of sociology, criminology and criminal justice. “That was the [common] assumption at that time point in the ’80s and ’90s.

“And so when we started looking at that first run of data, I thought there was something wrong.”

The data showed that immigrants — legal and illegal — were having a positive effect on their communities. Those findings are collected in his book, “Latino Homicide: Immigration, Violence, and Community.”

“We found something that was opposite to what we thought,” Martinez says. “We found that more Latinos meant less violence in many communities across the United States.”

Martinez and his Northeastern colleague Jacob Stowell, who rank among the leading experts in the field, say their research over the past three decades has disproved assertions that immigration exposes American communities to increases in crime.

“There aren’t a whole lot of things in my understanding that are the complete opposite of what people believe,” Stowell, a Northeastern associate professor of criminology and criminal justice, says of the immigration debate. “This is one of them.”

The ongoing migrant crisis on the Mexico border is helping feed the polarized U.S. debate over immigration, Stowell says. Criticisms are often tied to sensational crimes.

“Those crimes are heartbreaking and they are tragic,” Stowell says. “They also are the exception to the rule.”

Immigration revitalization hypothesis

Stowell says his research on the relationship between immigration and crime was inspired in no small part by his experiences growing up in San Diego.

“Generally there was a negative impression about immigration and its consequences socially,” he says.

In college, Stowell was employed as a waiter and many of his co-workers were immigrants.

“The folks that I worked with were hardworking and family oriented,” he says. “Some of them were working two full-time jobs. The public sentiment didn’t correspond with what I was seeing and my own belief.”

In 2009, Stowell published landmark research that found immigration was contributing significantly to the reduction in crime that the U.S. has been experiencing since the 1990s — a “great crime drop” that is continuing for a third straight decade.

Stowell’s findings were featured years later in a segment on “The Daily Show.”

Difficult to count population reliably

Are immigrants who enter the U.S. illegally more likely to commit crime than those who arrive by legal means? Stowell acknowledges that this issue has been problematic for scholars.

“It is very difficult to count this population reliably,” Stowell says of undocumented immigrants. “The Census, for example, is charged with counting the number of people in the country but does not ask about legal status, which makes it difficult research-wise.”

Using other analytical techniques, however, Stowell says researchers have found that the positive dynamic remains true regardless of how immigrants enter the U.S.

“The picture is generally the same: It appears to be the story that more immigration of any kind — legal or otherwise — is tied to lower levels of crime,” Stowell says. “There is no compelling empirical evidence that [illegal] immigration is positively associated with crime.”

The research efforts of Martinez and Stowell have been in line with studies by fellow scholars affirming the positives of immigration. The painstaking work requires data from the U.S. census to be matched with neighborhood crime reports.

‘The exception to the rule’

Stowell says the anti-immigrant language of today echoes back throughout U.S. history.

“The things people used to be saying about Polish immigrants are the same things they’re saying today about Latino immigrants,” Stowell says, citing previous anti-immigration rhetoric that scapegoated Germans, Italians, Irish and other ethnicities.

“There’s a supplanting of one group with another when people start talking about things like the undoing of the fabric of America at its core,” he says. “These broadly based statements get a lot of traction because of their grandiosity and not because of their substance.”

Stowell says it’s important to note the difference between first-generation immigrants and their offspring who are raised in the U.S. culture.

Featured Posts

“For the children of immigrants, their [criminal] patterns look much different from immigrants — they look more like the patterns of native-born Americans,” Stowell says. “In this sense becoming more American means becoming more criminal.

“And then the third generation — the grandchildren of immigrants — is indistinguishable from other groups,” Stowell says of their likelihood to commit crime. “I think a lot of times that folks conflate ethnicity and nativity, as if these two things are interchangeable. And the research is very clear on this point: Nativity and ancestry are not the same.”

Need for immigrants’ skills

The truth about immigration was hard to come by when Martinez was beginning his research three decades ago in the pre-digital era.

“This is something I did by hand — in the 1990s we didn’t have access to the laptops and scanners that we have today,” Martinez says. “I had to go into police departments and print information out on departmental copiers and carry some of that information back.”

The breakthrough in Martinez’s understanding came in Florida, a nexus of Latino immigration.

“I was fortunate to get access to the city of Miami[-Dade] Police Department and then it just took on a life of its own,” Martinez says of his research.

Martinez is now extending his study back to the 1950s and beyond.

“It was during that period [after World War II] in which we started to see the public recognizing that there were large Mexican-American communities and Puerto Rican communities across the United States, as well as the initial growth of the Cuban influx into Miami,” Martinez says.

Positive trends of immigration

Martinez says he finds the positive trends of immigration holding steady as he goes back in time.

“We are still seeing the clear and consistent effect that more immigration means less crime — and especially less homicide — in places where Latinos live and in places where we do have crime,” Martinez says. “It’s clear and consistent that we do not see higher levels of violence in those areas where immigrants have moved into.”

The U.S. needs immigration, Martinez says.

“Immigrants stabilize communities,” Martinez says. “If you look at people who work in low-skilled positions — if we’re talking about picking crops or working in slaughterhouses — those are skills that immigrants have developed over time that most Americans don’t have. Americans don’t want to work in those types of occupations. The immigrants we refer to as ‘lower skilled’ are important and vital to the United States and our everyday lives.”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News features writer. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.